Venues like the Bolshoy Ice Dome and Fisht Stadium have dazzled athletes and fans alike during the Olympics in Sochi. But what will become of them when the Olympic flame is extinguished and time marches on?

The arenas, ice rinks and ski slopes, which took years and cost billions to construct, are expected to be used for future sporting events and concerts. For example, 40,000-seat Fisht Stadium, the site of the Opening and Closing Ceremonies, will serve as one of the sites during the 2018 World Cup soccer tournament in Russia as well as a training center for future Winter Olympians and a concert venue.

As for the Alpine village of Rosa Khutor near Sochi, Russia is banking that it will become an international ski destination for tourists.

Watch video: What happens to Sochi after the Games?

The most expensive Olympics ever at $51 billion, Sochi hopes to avoid the pitfalls of host cities of the past.

The 2004 Summer Games in Athens are often cited as having built some of the biggest post-Olympic venue failures. Greece built nearly two dozen facilities for the Games. Ten years later, many of them have been abandoned or are rarely used.

“Most of them have chain-linked fence around them and they’re covered with graffiti. It was a waste of billions of dollars,” Gary Hustwit of documentary project The Olympic City told TODAY.com. Along with fellow photojournalist Jon Pack, Hustwit visited 13 former host cities to chronicle what happens after the Olympics have left.

Shortly after the Athens Games, Greece plunged into a deep economic recession that further stoked public anger over the government’s lack of foresight. After the downturn, the Olympics became “very symbolic of the government’s waste,” Hustwit said.

But many host sites — especially those cities that needed the infrastructure buildup triggered by Olympics-related development — have turned the Games to their advantage.

Barcelona, home of the 1992 Summer Games, wanted to revitalize its run-down industrial waterfront for decades before it won an Olympic bid.

“Using the Olympics as a catalyst, they completely redeveloped it. It’s reconnected the city to the water, and it’s this beautiful beach and a huge tourist draw,” Hustwit said. “In that case, they used the Olympics to do things they planned on doing anyway. They just didn’t redevelop the beach just to have a two-week party.”

The biggest key to setting up success for a city after an Olympic closing is simply having a plan, said Lisa Delpy Neirotti, a sports management professor who just returned from Sochi, where she attended her 17th consecutive Olympic Games (the 1984 Winter Games in Sarajevo were her first).

Neirotti, who teaches at George Washington University’s business school, recalled getting a call from tourism officials in Athens less than two months before the start of the Summer Games asking for advice on how to utilize Olympic facilities once they were over.

“I told them, ‘You’re a little late.’ It really starts from the bid perspective. You have to think it out even before that point,” she said.

In Beijing, host to the 2008 Summer Games, the Chinese government struggles to fill its “Bird’s Nest” stadium, which cost $480 million to build and $11 million a year to maintain. Now seating 80,000 (after 11,000 temporary seats were removed following the 2008 Games), the site has become a tourist attraction, but lacks a regular tenant.

Nearby at the city’s National Aquatics Center, the "Water Cube” now partly houses a public water park, said Neirotti, who visited the site.

“I saw hundreds of kids being trained how to swim there, and they turned one part of it into a slide area,” she told TODAY.com.

Closer to home, Atlanta gleaned numerous benefits from the 1996 Olympics. The former Olympic Stadium became Turner Field, home of the Atlanta Braves. The aquatic center used for Olympic swimming and diving events now houses similar competitions for Georgia Tech University teams. Other Olympic buildings were converted into university dorms.

“I estimate the city made half a billion dollars just because of the infrastructure benefits they received from the Olympics, and all those venues continue to be in use today,” said Neirotti, who teaches a class on Olympic Games.

Winter Olympic venues in particular run the risk of becoming white elephants, thanks to their high price tags.

“It’s a sad story,’’ author and historian David C. Antonucci told TODAY.com. “Either many venues just are no longer economically sustainable, or they are overtaken by technology or size.”

Antonucci is the author of “Snowball's Chance: The Story of the 1960 Olympic Winter Games Squaw Valley & Lake Tahoe.” He also has been involved in creating a museum to preserve the history of the 1960 Winter Olympics.

The original Alpine ski courses in Squaw Valley are still in operation, but Blyth Arena, the centerpiece of the Games, collapsed from excessive snow in 1982 and was destroyed. The ski jump fell into disrepair and became outdated.

The centralized Athletes’ Village, the first of its kind, was operated by the state of California after the Olympics, then sold to a developer and remodeled into time-share condominiums. The Opening and Closing Ceremonies were overseen by Walt Disney, but all that remains of his work is the head from a sculpture of a ski jumper, according to Antonucci.

Bigger crowds and better athletes also rendered Squaw Valley’s facilities obsolete.

“Blyth Arena only sat 8,500, which is way too small to host a hockey game now,’’ Antonucci said. “Also, ski jumpers just became more adept at what they were doing and jumped longer distances, so the ski jump was no longer suitable or safe.”

Mindful of mistakes by previous host nations, the Vancouver Organizing Committee from 2010 set aside a $110 million legacy fund for the Whistler Sliding Center, Whistler Olympic park and the Richmond Speedskating Oval. Four years since the Olympics left town, the venues are in relatively good shape.

The Pacific Coliseum, which housed the figure skating and short-track speedskating events in 2010, is home to the Western Hockey League’s Vancouver Giants and also hosts 40 concerts and other events annually, according to the Vancouver Sun. The Whistler Sliding Sports Center has become a training hub for luge, bobsled and skeleton. The Richmond Speedskating Oval generated a $3 million surplus in 2012 and attracts more than 700,000 visitors a year by hosting a variety of championship events, according to the Sun.

Many venues were returned to private ownership, and some alterations have been made. For instance, the snowboarding halfpipe at Cypress Mountain Resort was removed and is now part of a skiing run. The nearly $1 billion Athletes’ Village's 1,100 housing units were put in control of the city of Vancouver in 2011, which could end up losing up to $290 million from them, according to the Vancouver Sun.

The venues from the Salt Lake City Games in 2002 have remained in regular use thanks to a $76 million endowment fund, the Utah Olympic Legacy Foundation.

“When we make the comment that the 2002 Games were successful, from a planning standpoint, there was the forethought to think about what we would do with the venues going forward,’’ Utah Olympic Legacy Foundation marketing director Sandy Chio told TODAY.com. “You have this three-week event, the biggest event in the world, but then what's next? From an organizing committee standpoint, that process was put in place as the Games were being planned, and the result is what we see today.”

The foundation runs the Olympic Park and Olympic Oval as nonprofits, with funding coming primarily from the fund and also some donations and fund-raising. The parks hold public activities like zip lines, an Alpine slide and public ice skating.

The venues in Turin, Italy, from 2006 have continued to be in use for events like the World Figure Skating Championships in 2010. The Games helped make Turin one of the top tourist destinations in Italy, and its Olympic facilities have hosted events like the 150th anniversary of Italy’s unification in 2011 and a display of the Shroud of Turin in 2010 that attracted more than a million visitors.

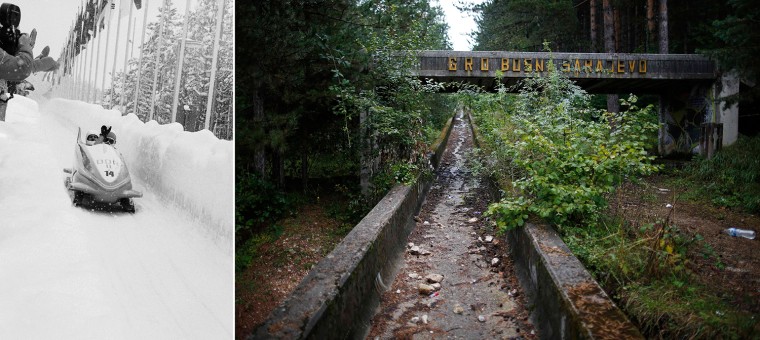

The most haunting former Olympic site is Sarajevo, which hosted the Games in 1984 in what was then Yugoslavia and what is now the capital of Bosnia and Herzegovina. A decade after the Games, many of the venues were destroyed or left to fall into disrepair as a result of the Bosnian war.

The bobsled venue served as a Bosnian-Serb artillery stronghold during the war, and now is mostly covered in graffiti and vegetation. The podium for the medal winners is riddled with bullet holes and was the site of executions. Some of the mountains that hosted Alpine skiing races are believed to still contain land mines, and Zetra Olympic Hall, which hosted the ice skating events, was destroyed by bombs. However, it was rebuilt in 1999 with the help of an $11.5 million donation from the International Olympic Committee and is now known as Olympic Hall Juan Antonio Samaranch, in honor of the seventh president of the International Olympic Committee.

Olympic villages, often problematic, have come in handy when they're built near college campuses. For example, in Calgary, Alberta, Canada, home of the 1988 Winter Games, five new buildings became part of the University of Calgary. And 20 low-rise apartment units built for the 2002 Winter Olympics in Salt Lake City later became housing for the University of Utah.

Host cities could take a lesson from the organizers of the Games in Chamonix, France, in 1924: Though the bobsled track and other tracks are no longer in use, the Olympic Stadium that housed sports like figure skating, hockey, curling, and speed skating as well as the Opening and Closing Ceremonies, still stands today and holds 45,000 spectators.